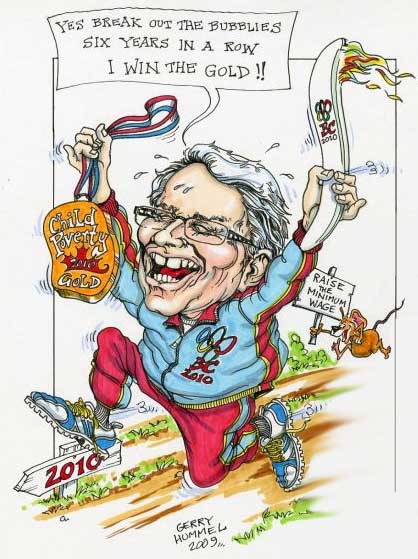

B.C. has Worst Child Poverty Rate in Canada Seven Years in a Row

© 2010 Brad Kempo B.A. LL.B.

Barrister & Solicitor

Millions continue to suffer as a result of systemic prosperity theft – some of which is being used to fund China’s global ambitions and some earmarked to keep Canada’s political and economic systems locked down for the benefit of the rich, powerful and Chinese. When given an opportunity to galvanize into a reform-motivated force many RCC invitees declined; an abdication of responsibility that not only speaks to the dysfunctionalities of these social justice and anti-poverty groups but also emboldens the malfeasant to accelerate their embezzlement. The most recent and glaring example is the $1.3 billion spent on June 2010’s three-day G8-G20.

It’s been said before so many times it's now trite, but it’s worth saying again: statistics and empirical research don’t lie. Despite being one of the richest countries in the world and an economy that more than doubled over the last quarter century, the most helpless in our society continue to take the brunt of a kind of wealth theft that dwarfs everything else during millennia of history.

The RCC invitation campaign involved edifying every group in the country that represents the poor and homeless about the true nature of Canadian governance and when the prosperity theft analysis was complete in late July 2010 that evidence was also delivered. During first contact and thereafter most of these associations declined to join the proposed national awareness initiative. Instead of fulfilling their mandates the RCC founder experienced the kinds of reactions documented in May 5, 2010: Is There Something Profoundly Dysfunctional With Some of Canada’s Anti-Poverty, Social Justice & Children Advocacy Organizations?, RCC News. So who’s at fault now beyond politicians, the richest of the rich and Chinese totalitarians and triads?

In 2006 child poverty was highest in BC for six straight years:

In 2007 child poverty was highest in BC for seven straight years. Why is this intolerable? Because the province continues to be in the 'have' category:

What are the have-not provinces of Canada?

October 24, 2010

There are 4 "have" provinces: British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland / Labrador. […] British Columbia … has been a "have" since about 2002.

B.C. has worst child-poverty rate in Canada

by Carlito Pablo

Georgia Straight

November 25, 2010

How do you like the idea of receiving regular income from the government, with no questions asked and no conditions attached?

The concept of a guaranteed income has been around for a long time, and child and youth advocate Adrienne Montani says it should be part of discussions on policies aimed at addressing poverty.

Montani made the suggestion on the sidelines of a Vancouver media event held on November 24, which showcased Statistics Canada figures indicating that for the seventh year in a row in 2008, British Columbia had the worst child-poverty rate in Canada, according to a measure of poverty that uses after-tax income.

“I like the idea of concentrating the kind of support that families would get into one payment,” Montani told the Georgia Straight. “The reason I like it is because right now, families don’t even know what they’re entitled to. And they [benefits] all start to fall away. Sometimes when you hit like $35,000 a year [in income], you lose your child-care subsidy, maybe. Your child tax benefit starts to go and you actually find yourself cash poor, and poorer than you would be if maybe you were not working.”

The adoption of a guaranteed income policy wasn’t included in the wide range of recommendations made by First Call: B.C. Child and Youth Advocacy Coalition in its latest report on child poverty. These recommendations include raising the minimum wage to $11 per hour and the federal government’s Canada Child Tax Benefit to $5,400 per child.

“Our coalition, First Call, hasn’t discussed it as a concept,” said Montani, a former Vancouver school trustee who is the provincial coordinator of the group.

However, Montani noted that she personally feels a guaranteed income policy would prevent families from losing benefits due to changes in their earnings. “If it was concentrated in one benefit, then you could have the coherence,” she said. “I like it that way.”

In November 2009, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives released a paper examining the concept.

James Mulvale, associate dean of the faculty of social work at the University of Regina, coauthored the paper with UBC law professor Margot Young. While the two have different views on the idea, they noted in Possibilities and Prospects: The Debate Over a Guaranteed Income that they both “agree that the question of ensuring universal, unconditional, and adequate economic security for all people in Canada is critical”. The paper also noted that proponents of the idea believe that such an approach is a “fix to poverty”.

In a phone interview from Regina, Mulvale explained that the concept of having an “unconditional, universal, adequate level of economic support for everybody” has many advantages “if it’s designed properly”.

According to Mulvale, the country’s separate systems of income support and welfare do not provide seamless support for people in need, and are often delivered on a piecemeal basis.

“We’re not doing a good job now, and we need to think about some other different approaches,” Mulvale told the Straight.

Tracy Johnson, a single parent, knows only too well the difficulty of getting by on limited means. Speaking during the presentation by First Call of its child-poverty report, Johnson explained that she is on welfare, and that she doesn’t have enough for her five children.

It isn’t just parents on welfare who are having a tough time, according to First Call’s report. The document also noted that the “vast majority” of B.C.’s 121,000 poor children live in families with some income from paid work. “In 2008, one-third of them - 40,600 children - lived in families with at least one adult working full-time, full-year,” the coalition’s report stated.

According to another paper coauthored by Mulvale, there are two basic guaranteed income models. One is the negative income-tax model, in which the government supplements incomes so people can rise above the poverty line. The second is the so-called “universal demogrant” model, in which all citizens receive a lump sum from the government.

The document, titled Income Security for All Canadians: Understanding Guaranteed Income, noted that the country has a long history of debates about this social model. It recounted how, during the 1930s, then Alberta premier William Aberhart sought to implement a system of regular cash payments from the provincial government to residents. However, this proved difficult to implement because of the economic depression at the time, as well as the federal government’s resistance to such a program.

Mulvale pointed out that at present, the country already has in place components of a guaranteed income system. He cited as examples the old-age pension, child tax benefits for low-income families, the rebate on the goods and services tax, and employment insurance.

“In terms of a strategy to move us towards something like a guaranteed income system…we need to take that step-by-step, incremental approach,” Mulvale said. “Others had argued that we could bring in one program that could replace all the other ones. I don’t think that’s politically feasible, and I also think it’s risky. Coming up with even a politically doable, a one-program-fits-all, and replaces everything else, I think that you might end up with people being worse off if they’re losing supports like health insurance and social housing and help for early childhood education.”

B.C.'s child-poverty rate worst in Canada for sixth year

by Carlito Pablo

Georgia Straight

June 4, 2009

The provincial coordinator of First Call: B.C. Child and Youth Advocacy Coalition isn’t optimistic that the improvement in the child-poverty rate in the province in 2007 will hold up, because of the recession.

“We expect the numbers to go up by the end of 2008,” Adrienne Montani told the Straight after her group took a look at the income figures for released by Statistics Canada on June 3.

According to First Call’s analysis, B.C.’s child-poverty rate fell to 13 percent in 2007 from 16.5 percent in 2006. Despite the decline, the province continued to have the worst child-poverty record across Canada for the sixth consecutive year. The 2007 rate is also higher than the national child-poverty rate of 9.5 percent.

In a phone interview, Montani noted that the economy was still doing well in 2007 but started to soften up in 2008.

“These last six years have been good economic times for this province, so a significant number of children and families were being left out of that prosperity,” Montani said. “It’s just not acceptable.”

There were 108,000 poor B.C. children in 2007 compared to 137,000 in 2006, according to a First Call news release. The release noted that the overall poverty rate in B.C. for all persons decreased from 13 percent in 2006 to 11.1 percent in 2007, “also the worst of any province” in Canada.

In its 2009 budget papers, the provincial government has acknowledged that the economy slowed down during the latter half of 2008, with B.C. experiencing job losses, lower consumer confidence, and slower business activity.

The finance ministry has estimated growth in 2008 at one percent. Things are expected to get worse this year, with the economy forecast to contract by 0.9 percent.

Child advocates like Montani have largely blamed cuts in social-program spending made by the B.C. Liberal government since it assumed power in 2001 as the main reason why child-poverty rates have worsened in the province.

In the run-up to this year’s May 12 election, First Call and other organizations urged political parties to adopt comprehensive antipoverty plans. They suggested special attention be given to those most likely to be living in poverty, like aboriginal people, people with disabilities and mental illness, those living in single-parent households, and recent immigrants and refugees.

With respect to child poverty, Montani said First Call has called for a reduction of 25 percent by 2012 and 50 percent by 2017.